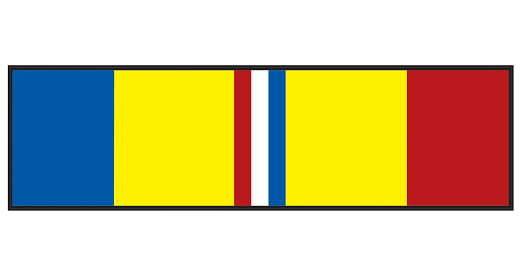

The Combat Action Ribbon (CAR) is a Navy and Marine Corps military decoration awarded to individual sailors or marines who, “have rendered satisfactory performance under enemy fire while actively participating in a ground or surface engagement.” This is probably the most coveted award for most marines. The ribbon is red on one side, blue on the other side, and yellow in the middle. It acts as a status symbol to validate the individual’s performance and worth as a war fighter-or so they think. Young marines fantasize about getting their first kill, being awarded the CAR, and being revered by their peers. Like many things we think we want, these marines are often disappointed and unfulfilled when they finally accomplish this goal. When you realize that taking someone else’s life doesn’t make your life any better, and you think about all the young talented men who had to die in service to our country for you to get that little piece of metal and fabric, you end up wishing you could just give it back and wipe the slate clean.

I saw my first CAR in the wild in August of 2002. Staff Sergeant Johns was a Gulf War veteran, an 0311 rifleman, and my J-Hat drill instructor. The Global War on Terror had just started and all the Vietnam veterans had retired so the only CARs in rotation were worn by Gulf War veterans who were aging at that point by Marine Corps standards. Johns had a big stack of ribbons that was four rows high, but that little red, yellow, and blue one stood out to every recruit in the platoon. He was universally respected and admired for other reasons, but not least was that ribbon on his chest.

Once I got into infantry school in the lead up to the initial invasion of Iraq, the marines would constantly talk about how exited they were to get their CARs. Our instructors complained that we would all soon get the decorations they wish they could have, but could not get because they were stuck training new marines. The day I got mine was anti-climactic and embarrassing when compared to all the stories we had learned about our predecessors in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam.

It was sometime in mid-April 2003 in Baghdad. U.S. and coalition forces had just run over the Iraqi military in a three-week race from Kuwait to Baghdad. Saddam Hussein’s army had mostly abandoned their bases and vehicles and fled back to their homes before we ever laid eyes on them. While I had seen some distant muzzle flashes, heard incoming rocket and artillery fire, and rode past many destroyed enemy tanks and buildings, I still had not fired a single shot. My platoon was in the capital city living in Saddam Hussein’s backyard and most of us had not even discharged our weapons. In our minds, the war was over and we would be going home soon with no CAR to show for it. Little did we know this war would be fought by Americans who weren’t even born when it started.

Like I said, we were camped out in the back yard of one of Saddam’s presidential palaces which was right on the Tigris River. It was late morning or early afternoon and most of the marines were barefoot in skivvy shirts and PT shorts trying to recover from the trench foot caused by our rubber chemical suit boots. We heard the crack of a rifle round go over the top of us and instead of seeking cover the way we were trained, the entire platoon of about 40 marines stood up and started looking around to see from where the shot came. A few seconds later we heard another coming from the opposite side of the river and then a third and final shot which allowed us to zero in on the source. A single vehicle, a civilian passenger car, had pulled up along the opposite side of the Tigris and the driver was taking pot shots at us from about 200 meters. In rifle shooting that’s what we call not that far. Our platoon commander called, “Designated marksman up!” This meant he wanted the three marines who were issued ACOG sights with 3x magnification to take the shot. The result was all 40 marines grabbed their rifles and machine guns and took up an online firing position along the river.

I heard the designated marksman begin to fire and saw the vehicle surge forward a few feet and then stop again. I looked to my left and saw another marine start shooting and I thought to myself this was probably my last chance. I placed my cheek against the buttstock, looked through the rear sight aperture, found the front sight post, and placed it on the center of the driver’s side door. My rifle was zeroed at 300 meters so I knew at this distance my rounds would impact a few inches above my point of aim. I sharpened my focus on the front sight allowing the car to become blurry in my vision. I made sure the clear front sight was centered inside the rear sight with a blurry target in the background. I moved my selector switch from “safe” to “fire,” wrapped my index finger around the trigger, waited for my natural respiratory pause, applied smooth steady pressure, and then BANG! Holy shit, it happened. I released the pressure until I heard an audible “clunk” and then squeezed again. Then again and again and again. I could hear the other M16’s starting to fire one by one. Then one machine gun, two more, three more, then all six. A cacophony of rifle and machine gun fire from all 40 marines filled the air and the little car across the river was ripped apart.

One of the complicating factors of a gun fight (not that this was a real fight) is that you cannot hear anything. Machine guns and rifles are much louder than you realize and this was a time when no one had suppressors or used hearing protection. I felt a kick on my leg and then heard a faint, “Cease fire! Cease fire!” I looked back and saw the platoon commander screaming at the marines to stop shooting. The shots died down and a few seconds later it was over. Everyone picked up their weapons and went back to sunbathing on the lawn just like before. We spent the next five uneventful months doing peace keeping operations. There would be more opportunities in the next few years, but that was the last of the shooting for this deployment.

I came home with a CAR and a case of imposter syndrome. I had been taught about the valiant warriors of the past and had hopes to relive some of their experience. Instead, I had spent seven months in a foreign land with very little war fighting and one fortieth of a kill to show for it. There would be more fighting to be had in subsequent deployments along with some maturity and a change of perspective on my part. In time I would stop associating self-worth with combat experience and look back at how ridiculous it all was.

Agree with you 100%